The Roots of the Crisis—and What We Must Do Now

Many of my global friends have messaged me about the recent talk of “genocide against Christians in Nigeria.

I hear the noise. I also carry the scars. I am from a northern minority (“Northern” Yoruba) Christian community.

See another personal story:

Hear from more Survivors: https://x.com/ogunmusi/status/1985626861943017841

Hear from Truth Nigeria Founder:

See more evidence: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-15262591/sickening-slaughter-Christians-Africa.html?ns_mchannel=rss&ns_campaign=1490&ito=social-twitter_mailonline

The USA has now come to the rescue: https://www.foxnews.com/video/6384574430112

Long ago, our ancestors chose Christianity under British rule. They sought protection after a late-1700s jihad reshaped the region. This event empowered new rulers around us.

As a child, I lived in an IDP camp in Kaduna. I watched our fathers take turns at night with clubs to guard our homes. At only 5 years, I experienced the trauma of watching pigs and dogs eat dead bodies on the streets of Kaduna and suffer PTSD to this day requiring therapy.

While living in Bauchi city, I saw my Sayawa friends leave for Bogoro to defend their families. Some came back hurt, but some never returned. My family left the North because of the killings. Many others could not.

On the highway, I was knocked out unconscious by Fulani Ethinic Militia members who left me for dead stealing my educational and birth certficates which I have never recovered to date. Many others perished , were kidnapped and never returned.

About ten years ago, while I was at Yale, I began sharing my story. I spoke about the trauma of growing up in Nigeria. As I talked, I watched some students’ eyes glaze over. It sounded like fiction to them—like a movie, not real life. But it was my life. I survived. Many did not. I carry their names in my heart, and it is my duty to speak for them.

This is why I am writing. I want to set the history in plain words. I also want to point us to actions that save lives—now.

I understand why the comments sparked debate. But I want us to focus on the real issue. People are dying. Communities are afraid. We need a plan that saves lives now.

I speak as someone with close proximity to this pain.

Let me tell just one story: While living in Bauchi (Northern Nigeria), my Sayawa friends left the city. They are indigenous Christians in Bauchi. They returned to their village homes. They wanted to protect their families. Some returned injured. Some did not return at all. My family eventually left the North. Many others could not.

These stories are not rare. For generations, Christian minorities across Nigeria’s Middle Belt and the far North regions have faced cycles of targeted violence—mass killings, kidnappings, and forced displacement—often during “infidel hunting seasons” when attacks become more frequent.

Let me be clear: Muslims, too, are victims of banditry, Boko Haram, ISWAP, and other criminal groups. However, the pattern of attacks on Northern Nigeria Christian communities is a persistent issue. It is a separate concern that has gone on for far too long. Local leaders and civic groups document these attacks well. The reality is simple and heartbreaking: ordinary people—farmers, teachers, traders, children—are not safe.

A Short History You Won’t See on a Talk Show

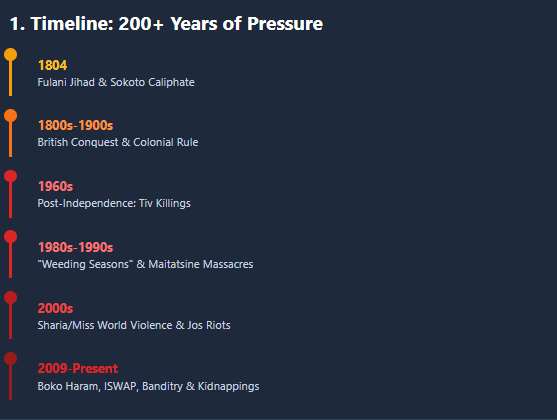

Two centuries of pressure.

Over 200 years ago, the Fulani-led jihad of Uthman dan Fodio built the Sokoto Caliphate across much of the North. Many older kingdoms were forced under its rule. Many people were enslaved.

The Oyo Empire—once a great savanna kingdom—grew weak. Northern Yorùbá towns faced raids. Many people were sold into slavery: some taken north across the Sahara, others sent south to the coast. Indigenous Hausa and other minorities suffered similar fates. This is one reason Brazil still has many people of Hausa and Yorùbá descent today. We Northern Yorubas lived at the edge of that caliphate, and yet we suffered immensely all the same.

Now, imagine the fate of indigenous traditional African religion worshipers who were stuck in the core of what is now Northern Nigeria. Many were enslaved, killed, or driven into the hills to survive. One example is the Koma people—living in remote highlands and only brought to wider attention in the 1990s.

In fact, this explains why you see that most indigenous non-Muslim minorities in Northern Nigeria live in the cliffs. They reside in the mountains. It was to survive.

The British later conquered the Caliphate. They noted how deeply some indigenous Hausa and minority groups feared their Fulani rulers. Their fear was so intense that they would not look them in the eye. A few strong peoples, like the Tiv and Jukun, resisted and survived. All of the indigenous Hausa kingdoms became vassals. Other kingdoms—like the Nupe—had their ruling houses “fulanized” and survived by being “islamized”. Other groups like the Igala saw mixed outcomes. The sustained Fulani jihad via its “fulanized” Nupe emirate eroded the powerful Igala power at its northern frontiers. This erosion also affected some of the Igala’s vassal states. Nevertheless, they did not replace the central Igala ruling house in Idah with Fulani rulers. Even long-Islamic Kanem-Borno was attacked, until Muhammad al-Kanemi pushed back.

This past still shapes today. Many northern minorities resisted the Caliphate. Later, under colonial rule, most Northern Nigeria minorities chose to become Christian. They made this choice after coming in contact with Christian missions. They also sought British protection as Christians to stay alive in a hostile predominantly moslem region.

Let me be clear: this is just historical facts. This does not make whole peoples “good” or “bad.” It shows how fear, power, and faith mixed in hard ways—and how small communities learned to live on guard. The ancestors of northern Nigerian Christian communities took steps to survive. This is how we became a Christian indigenous minority in what became a predominantly Muslim region.

Post-colonial crackdowns and waves of violence.

After independence, pressure on minority communities did not end. In the 1960s, Tiv communities faced large-scale killings. Through the 1980s and 1990s, the Middle Belt and Southern Kaduna saw repeated clashes. I survived the Zangon-Kataf massacres in 1992. Many of us remember “weeding seasons,” when attacks on Christian villages spiked and families fled to camps.

Many southern Nigerians only became truly enraged when their own kin were killed in the major Maitatsine massacres of the 1980s and the Sharia/Miss World-related violence of the 2000s across Northern Nigeria.

I still remember how many of my indigenous Christian friends at the University of Jos were killed on campus during the 2000s riots. Yet for every southerner killed, several more indigenous northern Christians lost their lives.

The insurgency era.

Since 2009, Boko Haram and later ISWAP burned towns, took hostages, and killed both Christians and Muslims. Bandit gangs spread kidnapping and fear across the Northwest and North-Central. Yet the pattern of targeting small Christian communities has remained a grim constant. The 2014 Chibok abductions—mostly Christian schoolgirls—became a global symbol. Sadly, many similar attacks before and after Chibok drew less attention but caused the same deep pain.

A warning from our region.

Think about Sudan and the crisis now unfolding in El Fasher in Sudan’s Darfur region.

For generations, the non-moslem South Sudan endured enslavement, exclusion, and violence within Sudan. During this time, the world looked away. Eventually, the injustices finally broke that country.

I do not wish that fate on Nigeria.

I share this as a warning: when a state ignores deep, layered harm against its minorities, the whole nation pays a higher price later.

We see it now in the spread of kidnappings and banditry across Nigeria. Not even the prosperous and peaceful Southwest Nigeria region is safe anymore. Our Southern Yoruba kinsmen live there as a majority. Yet they are no more safe. Even the graves of their ancestors in the Old Oyo national parks is being desecrated by Northern-origin bandits. And they are all quiet.

The country is drifting toward a Hobbesian state, not unlike the chaos before British conquest in the 1800s—mass killings, and a new kind of slavery where kidnapped people are no longer sold, but ransomed for cash.

What the Noise over Trump Misses

Whether a famous person says the right words is not my main concern. What matters is protection. Nigeria suffers “war-level” harm without a formal war: mass displacement, frequent killings, and the silent deaths of children and mothers.

Many watchdog groups say Nigeria has the highest number of Christians killed for their faith in recent years. Muslims also suffer greatly under terrorists and bandits. Two truths can stand together:

- Christians in parts of the North and Middle Belt face targeted violence; and

- many Hausa, Fulani, and other Muslim families are also victims.

Blaming entire peoples will not keep a single child safe. Targeting perpetrators and their networks will.

Let’s separate the headline from the hard work that needs to be done

I am less interested in who said what on TV than I am in what we do next. If a high-profile comment shines a light on the suffering of Nigeria’s minorities, good. But awareness is only step one. We must turn attention into protection.

Nigeria faces “war-level” harm without a formal war. High child and maternal deaths, mass displacement, and constant fear create a heavy toll on life. When a state can’t guarantee basic safety on roads, the social contract is broken. It breaks in farms, in schools, and in places of worship. Fixing that must be our shared national mission—across faith, ethnicity, and party.

What I’ve learned from a lifetime of proximity

- This didn’t start yesterday. Attacks on minority communities in the North and Middle Belt have deep historical roots. Old power struggles, land pressure, and today’s criminal economies all feed the fire.

- Collective blame makes things worse. Entire ethnic groups or faiths are not the enemy. Many Hausa and Fulani families also suffer at the hands of violent actors. We must target perpetrators and networks—not label whole peoples.

- Silencing voices keeps the cycle going. Journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens who speak up have faced threats and harassment. When truth is punished, violence spreads in the dark.

- Data and empathy must walk together. Numbers help us see scale. Stories help us feel urgency. We need both to design solutions that fit local realities.

A practical plan to protect lives now

Here is what I believe can work—instantly and over time:

- Name and track the violence precisely.

- Build a national, independent incident registry that verifies attacks by location, method, victim group, and likely perpetrators.

- Publish weekly heat maps for governors, traditional rulers, and local police. If we cannot measure it, we cannot manage it.

- Protect the most exposed communities fast.

- Ring-fence hot spots with joint security task forces that include federal, state, and vetted local actors under one command.

- Prioritize school routes, farm corridors, and worship days with visible patrols and rapid-response units.

- Create community shelters with radio alerts and clear evacuation plans.

- Cut the money and tools of violence.

- Track ransom flows, illegal mining revenues, and gun routes with financial-intelligence units and cross-border partners.

- Seize weapons and prosecute gunrunners—consistently and publicly.

- Use simple tech that works offline.

- Set up USSD/SMS hotlines for early warning in low-connectivity villages.

- Use lightweight apps for anonymous tips, with rewards for verified leads.

- Map farm conflict lines and grazing paths to guide negotiated de-escalation.

- Support victims with dignity.

- Guarantee medical care, trauma counseling, and safe housing for survivors and IDPs—including documentation to access aid and rebuild.

- Protect girls and women from re-trafficking; establish specialized survivor units in every affected state.

- Put local leaders at the center.

- Convene clergy, emirs/chiefs, youth groups, and women leaders to co-design security protocols and social peace deals.

- Back agreements with real incentives: access to markets, schools, clinics, and water projects when violence stops.

- Tell the truth—without hate.

- Uphold free reporting and community testimony while rejecting incitement.

- Train spokespersons who can speak clearly about targeted attacks on Christians and other minorities without fueling revenge narratives.

- Invite help and accept accountability.

- Request technical assistance from partners for forensic investigation, kidnap-for-ransom disruption, and victim services.

- Welcome independent reviews and public scorecards so progress is visible and trust can grow.

On the “G word”

People ask if what is happening to Christian minorities in parts of Northern Nigeria is genocide. The term has strict legal meaning. Investigators must determine that. What I can say is this: the centuries-long pattern of targeting, the scale of killings and kidnappings, and the intent to erase northern christian communities from their lands meet many warning signs. We should not wait on a debate over labels to act. We must protect people now.

A 90-Day Playbook (and What Follows)

In the next 90 days:

- Track every attack, publicly.

Create an independent incident log with village-level details. Post weekly heat maps so governors, chiefs, emirs, clergy, and police act on the same facts. - Protect the most exposed places.

Put joint security teams around hotspot LGAs. Guard farm corridors, school routes, and worship days. Stand up rapid-response units with one command and clear rules. - Disrupt the money and guns.

Follow ransom payments, illegal mining funds, and gun routes. Freeze accounts. Seize weapons. Prosecute gunrunners—consistently and on record. - Use simple tech that works offline.

Launch USSD/SMS hotlines for early warnings in villages. Offer rewards for verified tips. Map farm-grazing routes to guide real, local ceasefires. - Care for survivors with dignity.

Guarantee medical care, trauma support, and safe shelter for IDPs. Protect girls and women from re-abduction. Issue IDs so families can access aid and rebuild.

In the next 12 months:

- Put local leaders at the center.

Clergy and traditional rulers should co-design safety plans. Tie peace deals to real gains—clinics, schools, wells, and market roads—delivered when violence drops. - Tell the truth without hate.

Protect reporters and community witnesses. Speak plainly about patterns of attacks on Christian minorities and on other civilians. Reject speeches that call for revenge. - Invite help—and accept checks.

Ask partners for forensics, kidnap-for-ransom disruption, and victim services. Publish scorecards so citizens can see progress and hold leaders to account.

Again On the Word “Genocide”

“Genocide” has a strict legal meaning. Investigators must judge that. The signs we see—targeting, scale, and the effort to drive communities off their lands—are serious. We should not wait on a courtroom label to act. The duty to protect is already here.

Why I Will Keep Speaking

I have buried friends. I have known the fear of the night watch. I have seen children in camps grow up with no clear future. Yes I lived such a camp.

So yes—if a global figure shines a light, I welcome that attention. But I am not here to win an argument on television. I am here to push for action. This action keeps families alive. It lets them live with dignity on their own land.

Leaders, show your plans for hotspot LGAs and report response times. Faith leaders, visit attacked villages together and stand together for life. Donors, fund the quiet basics—data, radios, shelters, clinics, courts. Builders and founders, create tools for early warning and safe reporting. Diaspora, sponsor a village safety kit or a survivor fund.

If you have lived this, tell me what else belongs in a 90-day plan. Let’s turn noise into protection—now.

My personal stance

Firstly, thank you to Trump and the USA. Special thanks to the evangelical christian community from the Western world. They deserve appreciation for speaking for the weak and forgotten christian minorities of Northern Nigeria. You did not have to yet you did and the Northern christian peoples of Nigeria will stay forever grateful.

Secondly, I respect anyone—famous or not—who uses their voice to highlight this crisis. Nevertheless, my focus is on solutions. I am not interested in political drama. If a global figure’s words help wake the world up, I will gladly use that attention. It can help push the Nigerian State toward action.

But I refuse to reduce this to the empty politics many Nigerians indulge in. This is just like the hullabaloo over Kemi Badenoch’s rightful comments about the Hobbesian state of affairs in Nigeria today.

Over time, I’ve realized something painful. Ordinary Nigerians are the ones suffering the most. Yet, they are often the ones resisting real solutions. For me, this comes down to two things.

First, a national Stockholm syndrome. People are emotionally attached to their oppressors. They are ashamed of their exploitation and too proud to ask for help.

Second, all the noise and outrage often serve as a distraction. This keeps us from doing the hard work of fixing the country. It is essential to make it safer and more just for the majority. This need is urgent. Today, that country hosts one of the largest concentrations of human suffering in the world. That distraction is often fueled by ruling elites who gain from the current exploitative system. They like to distract the youth from their failings as rulers. They do this by bringing up past colonization wounds and so-called Western imperialism. The primary problem today of the poor Nigerian is not some white man somewhere. It is the local black rulers. They have exploited their people for an extended period. Their actions are so egregious that they will make the western passage slave traders of the 1800s feel ashamed.

The poor of Nigeria will welcome help from anywhere. Hell yeah! Let the British come back and colonize the whole country. This is acceptable if it means fewer people dying and suffering needlessly as they presently are. Poor Nigerians need HELP!

Any humanist concerned about the global state of humanity should not ignore Nigeria. Anyone wanting to improve it can’t afford to look away.

For me, this is about my neighbors in Kaduna and Bauchi. It is about children who deserve to grow up. It is also about the many Nigerians—Christian and Muslim—who want nothing more than peace and a fair chance at life.

Audu Maikori was silenced a few years ago when he spoke about this. I remember that event well. So, I’m not naive about the risk I’m taking now. But I come from a clan that has fought against this oppression for 200+ years. I still remember the last time someone called me from back home. They were asking me not to keep quiet. I owe my ancestors. I owe the long suffering Northern christian peoples who continue to suffer these injustices. I choose not to be silent.

I owe the future children of this region of Nigeria a clear understanding of the history of this crisis. The rest of Nigeria and the wider world also deserve this knowledge. This will help us solve it better.

All people carry the potential for both good and evil. We can end evil by shining light on it.

Muslims, Christians, traditional worshipers, and atheists alike ultimately want the same thing: for human lives to matter.

A call to leaders—and to all of us

Governors and security chiefs: publish your hotspot plans and response times. Faith leaders: meet together, visit attacked villages together, and stand as one for life. Donors and partners: fund the boring but vital basics—data, radios, shelters, clinics, and courts. Tech founders: build tools for early warning and safe reporting. Diaspora: sponsor a village safety kit and a survivor fund.

Let’s turn noise into protection, and attention into outcomes that families can feel in their daily lives.

What did I miss? If you’ve lived this, what would you add to make communities safer within 90 days? I’m listening.

#umbrasuggero

Discover more from Adebayo Alonge

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“When a state ignores deep, layered harm against its minorities, the whole nation pays a higher price later.”

I sincerely wish every Nigerian would read this article, and most of all, I wish the leaders would pay attention to the action plan meticulously and elaborately enumerated in it.

Thank you for lending your voice to this.

Thank you—your words mean a lot. Please share the article with your network and tag leaders who can act. If you can, send it to your reps and ask for a 15-minute staff call on the 90-day plan—track attacks, guard hotspots, and care for survivors. I’m ready to brief anytime. #umbrasuggero