After traveling to 70+ countries and reading Jacqueline Novogratz’s The Blue Sweater, I’m left with a profound unease about the development industry’s approach to poverty. Yes, the book offers valuable lessons about moral imagination and distributed leadership. But it also reveals a troubling blindness that pervades much of the “patient capital” movement.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Representation

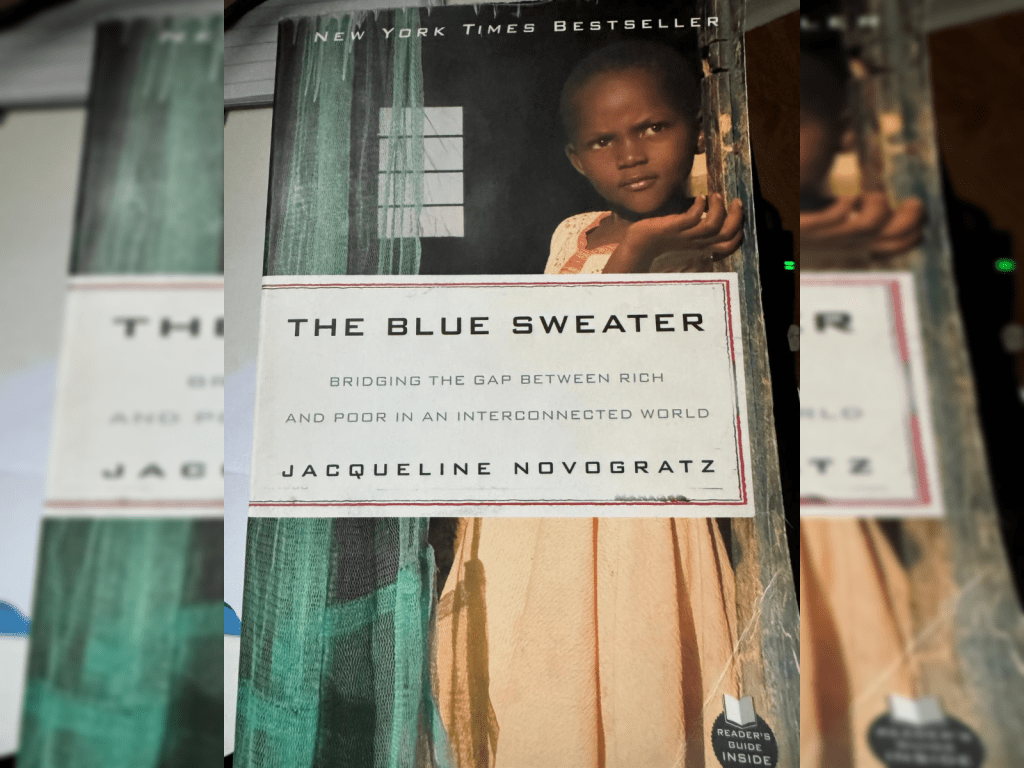

Let’s start with what we don’t talk about enough: the book’s cover features a Black African child in the context of poverty—a visual trope that has been exploited for decades. Did that child receive royalties? Was there informed consent about how their image would be used globally? These questions matter because they expose the power dynamics that the book itself fails to examine.

Novogratz writes about being welcomed into native dances and community spaces across Africa, yet offers little reflection on why those doors opened so readily. The uncomfortable reality? Her white skin carried prestige and privilege that shaped every interaction. Without acknowledging this, the narrative becomes another story of a Western savior rather than a critical examination of how development work perpetuates the very hierarchies it claims to dismantle.

What The Blue Sweater Gets Right

Despite these blind spots, the book offers two powerful insights:

1. Moral Imagination

The ability to genuinely put yourself in another’s shoes is devastatingly absent in today’s world. It’s why violence spreads. It’s why policy fails the vulnerable. It’s why poverty persists even as global wealth grows. When we lose the capacity to imagine another person’s lived reality, we lose our humanity.

2. Distributed Leadership

The most effective teams aren’t built on command-and-control. Give people a clear direction and the autonomy to achieve it. Strong personalities often believe it’s “my way or the highway,” but high-performing teams thrive when each person has genuine agency within a shared vision. Micromanagement kills innovation. Trust unlocks it.

The Fatal Flaw: Markets Cannot Fix Cultural Oppression

Here’s where my skepticism crystalizes into certainty: after half a century of “patient capital,” poverty has increased everywhere except Scandinavia and China.

The development industry keeps insisting that markets and entrepreneurship will solve poverty. I bought into this narrative myself. But experience has taught me something crucial: markets help the vulnerable poor—those with some capital who need market discipline to avoid falling into poverty. Markets do not reach the truly poor.

Why? Because the deepest poverty isn’t a market failure. It’s a human creation.

Poverty is Cultural Exploitation, Not Just Economic Deprivation

The truly poor are made so by deliberate systems of oppression:

- In India: the caste system creates an underclass to exploit

- In Arab and African countries: ethnic and religious hierarchies determine opportunity

- In the West: race and class construct invisible barriers to wealth accumulation

These are not problems that entrepreneurship can solve. These are human-created problems that require human solutions.

True poverty is cultural subjugation matched with economic exploitation. Even in communist states where markets theoretically don’t exist, the poor remain poor because ruling classes hoard wealth and power.

What Actually Works: The China and Scandinavia Model

The most peaceful, equitable societies I’ve encountered share a common approach: ruling classes who prioritize the vulnerable through both market discipline AND social redistribution.

Not markets alone. Not state control alone. Both.

Markets cannot solve problems created by cultural exploitation—that requires government intervention and social transformation. And markets cannot self-correct when people lack the basic resources to participate—that requires redistribution to give everyone a genuine chance.

A Challenge to Development Experts

Stop digging the same hole deeper.

The ideology that markets alone will solve poverty has failed for 50 years. The patient capital movement has noble intentions but refuses to confront the cultural and political systems that create poverty in the first place.

Real solutions start small:

- Stop using images of African children to discuss poverty

- Stop subjugating people based on race, gender, sexual orientation, or religion

- Acknowledge that your skin color, passport, and access created opportunities that others don’t have

- Recognize that cultural change must precede—or at least accompany—economic intervention

The Path Forward

I’m not arguing for abandoning markets or entrepreneurship. I’m arguing for honesty about their limitations.

If development work is to matter, it must:

- Confront how cultural oppression creates and maintains poverty

- Acknowledge the privilege and power dynamics inherent in cross-cultural “help”

- Combine market discipline with aggressive redistribution

- Center the voices and leadership of those experiencing poverty, not outside experts

- Measure success not by businesses created but by systems of oppression dismantled

The Blue Sweater offers valuable reflections on empathy and leadership. But until the development industry can look in the mirror and see its own complicity in the systems it claims to fight, we’ll keep getting books that inspire without transforming, that comfort without challenging, that perpetuate the very dynamics they claim to solve.

What are your experiences with development work, social entrepreneurship, or poverty alleviation? Where have you seen approaches that genuinely address systemic oppression rather than just market failures?

Discover more from Adebayo Alonge

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.